Much of the best academic research on rape over the past decade, in South Africa and globally, has focused explicitly on men, the primary perpetrators of sexual violence. Such efforts have resulted in truly important work; understanding why men rape is essential to combatting sexual violence. Furthermore, focusing on rapists helps hold them to account. Rape is often reported as a ‘perpetrator-less crime’, with undue attention paid to female victims – where they were, what they were wearing, or how they were behaving – rather than the men who most commonly inflict this violence. [1] Joanna Bourke contends that ‘it would be wrong to explore the violence carried out predominantly by men by studying the women they wound,’ arguing that doing so may only perpetuate tendencies to blame women for their own violation. [2] When specific research on rape in South Africa began in the 1990s, the primary focus was also on the rapist. [3] More recently, researchers have tried to establish exactly who the country’s rapists are, interviewing men from across various class, educational, and ethnic backgrounds, and why they commit this violence, exploring theories of masculinities ‘in crisis’, past-perpetrator trauma, socio-economic exclusion, and patriarchal gender norms. [4]

So why does this project aim to do the opposite, and focus explicitly on women’s histories of sexual violence in South Africa?

First, because women’s own perspectives on sexual violence have so often been silenced. At times, this silencing is very public, such as in the 2006 rape trial of former president Jacob Zuma, in which his accuser, ‘Khwezi’, had her experiences of her own rape silenced, questioned, and disregarded. We currently know very little about how South African women have conceptualised, experienced, or responded to sexual violence over the course of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. As the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation recently highlighted, this means that current explanations of rape in South Africa have been developed ‘independent of women’s actual experiences or, at best, may have been informed by limited fragments of such experiences.’ [5]

Furthermore, when men’s violent behaviour today is explained as a consequence of South Africa’s racist and violent past, it creates a tendency to see the harmful effects of racial oppression as impacting men only. As Denise Buiten and Kammila Naidoo argue, ‘what is left unproblematic is how the consequences of these violent pasts are highly gendered, and the ways in which many women are victimized (not just by men but also by the very structures that also victimized black men).’ [6]

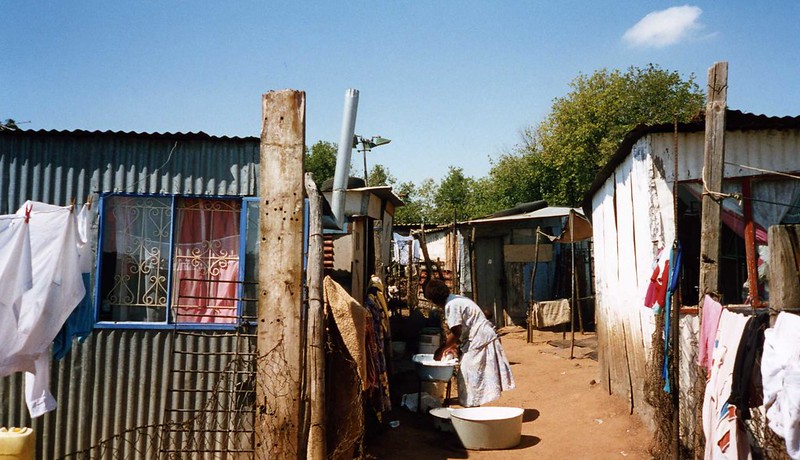

Second, understanding how South African women’s lives have (or have not) been shaped by fears or experiences of sexual violence provides us with a much fuller picture of women’s histories during and after apartheid. From what the existing scholarship does tell us, black urban women were subjected to astonishing levels of violence by men from at least the 1940s onwards. Historians talk vaguely about rape and abduction being ‘extraordinarily common’ in the 1940s and 50s, without further exploration of what this meant for women’s lives. [7] In 1981, writer Miriam Tlali set out to interview women in Soweto about the township’s seemingly escalating rape problem and concluded that, ‘virtually all black women, from small children to grandmothers and great-grandmothers, live in perpetual fear and are haunted by the lurking shadow of possible personal defilement. [8]

This suggests that women’s everyday lives and activities, both within and outside the home, were likely shaped by the threat of sexual violence. In order to fully understand the history of women’s labour, political activism, religious beliefs, relationships, or family lives, we thus also need to better understand how women themselves conceptualised, experienced, and responded to this threat. On the other hand, if women did not live in daily fear of violence, or if these fears were subordinated to quotidian struggles for money, shelter, or political freedom, then this also tells us much about women’s histories. This project does not explore sexual violence in a vacuum removed from other forms of violence and discrimination, but sees it as being inextricably linked to other facets of women and men’s lives. It will thus examine histories of sexual violence indirectly as well as directly, through the lenses of romantic relationships, crime and gangsterism, economic struggles, the apartheid state and the liberation struggle against it.

If we can know more about how women have understood and experienced sexual violence over the past century, then we can better understand their agency, relationships, needs and desires – knowledge that is essential to creating more informed violence prevention programmes. Attempts to tackle gender-based violence in South Africa must also consider the country’s historical complexities, and how these have affected women as well as men.

[1] Pumla Dineo Gqola, Rape: A South African Nightmare (Johannesburg, 2015), 7.

[2] Joanna Bourke, Rape: A History from 1860 to the Present Day (London, 2008), 5.

[3] Lloyed Vogelman, The Sexual Face of Violence: Rapists on Rape (Johannesburg, 1990).

[4] Rachel Jewkes et al., ‘Why, When and How Men Rape: Understanding Rape Perpetration in South Africa,’ South African Crime Quarterly 34 (2010): 23-31; Louise du Toit, ‘Shifting Meanings of Postconflict Sexual Violence in South Africa,’ Signs 40:1 (2014): 101-123.

[5] Nonhlanhla Sibanda-Moyo et al., ‘Violence against Women in South Africa: A Country in Crisis,’ CSVR (2017), 14.

[6] Denise Buiten and Kammila Naidoo, ‘Framing the Problem of Rape in South Africa: Gender, Race, Class and State Histories,’ Current Sociology 64:4 (2016): 541.

[7] Clive Glaser, ‘The Mark of Zorro: Sexuality and Gender Relations in the Tsotsi Subculture on the Witwatersrand,’ African Studies 51:1 (1992): 59; Anne Mager and Gary Minkley, ‘Reaping the Whirlwind: The East London Riots of 1952,’ in P. Bonner, P. Delius and D. Posel (eds), Apartheid’s Genesis: 1935-1962 (Johannesburg, 1993), 237.

[8] Miriam Tlali, ‘Rape – and the Terror,’ Rand Daily Mail, 7th May 1981.