Erin Hazan and Emily Bridger

There is no crime more difficult to prove than rape and no injured party more distrusted than the rape victim.[1]

On 11 January 2021, popular South African DJs Fresh and Euphonik were accused of drugging and sexually assaulting Siphelele Madikizela in 2011.[2] This was not the first instance where either man was accused of gender-based violence. In 2012, Bonang Matheba laid charges against Euphonik of assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm, malicious damage to property, and housebreaking with the intention to assault.[3] She subsequently dropped the charges after the couple reconciled (they have since split permanently). When Matheba laid the charges, she was broadly accused of lying. In a 2017 interview she stated, ‘I was embarrassed, humiliated and ill-prepared in how to deal with my very first scandal. To this day I am called a liar.’[4] As for Fresh, in 2019, a woman anonymously accused him of rape eighteen years prior, and in 2020 poet and activist Ntsiki Mazwai accused him via Facebook of being a rapist. Fresh sued Mazwai for defamation and won.[5] On 19 February 2021, a third woman accused Fresh of rape via Twitter.[6]

In the most recent case of accusations against the DJs, the National Prosecuting Authority decided not to prosecute the case based on ‘insufficient’ evidence. Shortly thereafter, the two men released a statement on the matter, reading:

…the Chief Prosecutor has dismissed the allegations on the basis that the allegations are without merit. The docket has been marked NOLLE PROSEQUI. As we’ve said before, these are false allegations and we are deeply saddened that GBV, a serious crisis in South Africa, was weaponised in this manner.[7]

The DJs’ statement neglected a key fact of the case: the NPA did not state that there was no evidence, nor that Fresh and Euphonik were innocent, but simply that the case will not be prosecuted. A 2008 Gauteng-based study revealed that only 42.8% of reported rape cases resulted with an offender being charged in court, and only 6.2% in a conviction.[8] In other parts of the world, conviction rates are even lower. The UK is currently witnessing its lowest conviction rate of any period on record, with only 2.6% of reported rapes securing a conviction.[9] It is thus irresponsible and incorrect to make the assumption that a case which wasn’t prosecuted or didn’t result in conviction equates to a false allegation made by a lying woman.

Yet this was the exact connection that the DJs and their supporters made. In Twitter responses to their statement, users argued that Madikizela was clearly a liar because she waited almost a decade to report the violence she suffered.[10] Since the NPA’s announcement, news articles attacking Madikizela for lying about being raped have emerged, with Euphonik fanning the flames, tweeting on 16 February 2021 that he is being attacked by ‘the toxic feminist brigade… [who] don’t know the difference between fact or fiction’ and that ‘you can’t rape someone you’ve never met.’[11] It is clear that whilst the docket has been labelled nolle prosequi (will no longer prosecute), Madikizela is being held liable in the court of public opinion.

By accusing Madikizela of weaponising GBV for her own benefit, Fresh and Euphonik have become part of a dangerous counter-narrative of victim blaming, victim shaming, and not believing women who come forward about sexual violence. In doing so, they contribute to a long history of men accusing women who ‘cry rape’ to be liars. Joanna Bourke identifies this as a central ‘rape myth’. Since at least the late 19th century, the idea that women are prone to lying about rape, and do so to enact revenge against men, has been widely believed despite having no basis in fact. In Victorian England, it was commonly assumed that somewhere between 80 and 99 per cent of rape allegations were false.[12]

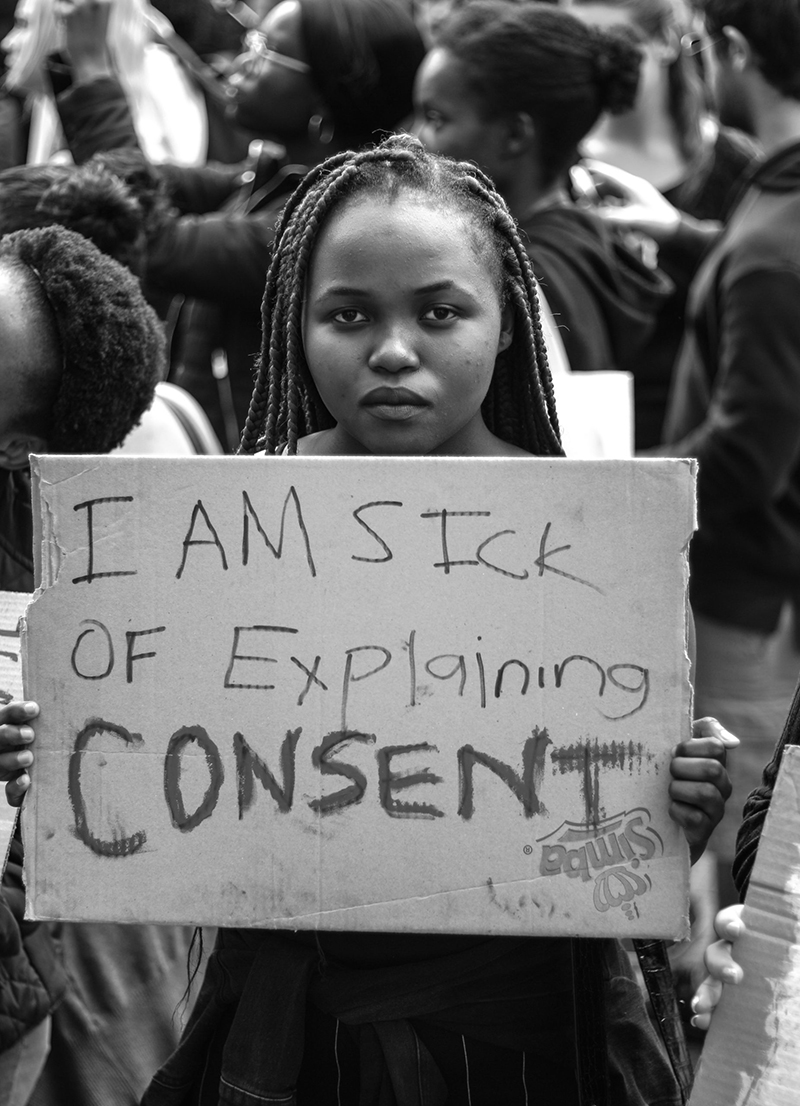

Ideas about which women tend to lie are also shaped by racial and class assumptions. In the US, Black women have historically faced greater disbelief than white women when reporting rape, due to police assumptions about their lack of credibility and racialised stereotypes about their presumed promiscuity.[13] Similarly in British colonial India, Indian women were also presumed to be deceitful and particularly likely to make false rape charges.[14] The same can be seen in the South African case, where colonial attitudes promoted a stereotype of Black hypersexuality. While Black men were cast as predatory and unable to control their sexual appetites, Black women were assumed to be ‘excessively sexual and impossible to satiate.’[15] This characterisation led to a societal understanding that it was ‘impossible’ to rape a black woman because her consent to any sex was deemed inconsequential.[16]

These colonial stereotypes have had lasting consequences and damaging implications for Black women across the apartheid and post-apartheid periods. In 1972, Justice Hiemstra presided over two similar rape cases, both concerning young female victims around 15-years-old and young Black male perpetrators who used weapons to intimidate their victims. One case, in which the victim was white, resulted in a 10-year prison sentence, while the other, in which the victim was African, received only four years. Hiemstra denied that this difference in sentencing had anything to do with race, before proceeding to explain his decision based on various factors that were all clearly linked to racial and class assumptions. One key point, he stated, was that the white girl had been a virgin before being attacked. Hiemstra justified that ‘The African girl in this case is someone who had relations with a man before. She denied it in the witness box, but I don’t believe her,’ thus constructing the girl as both a liar and more promiscuous than her white counterpart.[17]

From the mid-1970s onwards, concern about rape began to escalate in South Africa, often becoming front-page news and a key topic of discussion within both white and black communities. However, in their approach to sexual violence in the townships, the police clung to this now-century old rape myth and continually belittled Black women who reported rape as liars. In 1977, Colonel PJ Visser, Chief of the Soweto Criminal Investigation Department (CID), stated that ‘100 women are raped in Soweto every month’. Visser further stated that ‘a large proportion of “rapes” are false reports by women who sleep away from their matrimonial beds. To exonerate themselves they tell their husbands that they were raped… this group represents 80 per cent of “rapes”.’[18] From 1982 to 1985 Soweto CID Chief Brigadier JJ Viktor also repeatedly defended the police’s rigorous questioning of rape victims as necessary, stating that many reported cases were false and a tactic used by girls caught sleeping over at their boyfriends’ houses.[19] By repeatedly constructing Black women as prone to lying about rape, the Soweto police missed an opportunity to effectively tackle the crime at a key moment in South African history when rape rates were escalating and communities were looking for solutions. Instead, the police’s words alienated women, encouraged them not to report, and perpetuated this key rape myth.

In the post-apartheid period, women have continued to be shamed for making rape reports. Most notoriously, in the 2006 rape trial of Jacob Zuma, his accuser ‘Khwezi’ was largely disparaged as a serial liar and maker of false rape claims.[20] It is important to locate the contemporary debates on rape and sexual violence within their historical, local and institutional contexts; to understand how the case of DJs Fresh and Euphonik form part of broader historical continuities and rely on centuries-old rape myths that still privilege the accused over their accusers. It is irresponsible to judge women as liars simply because their cases are not taken to trial. At a time when many countries around the world are seeing their prosecution and conviction rates for rape decline year on year, we cannot allow the majority of rape victims who are already denied justice to also be branded as ‘liars’, or for other women to be dissuaded from reporting sexual violence out of the fear that they will face the same public humiliation.

[1] Joanna Bourke, Rape: A History from 1860 to the Present (London: Virago, 2007), 23.

[2] Storm Simpson, ‘Police confirm rape case opened against DJ Fresh and Euphonik,’ Capetownetc., 15 January 2021.

[3] Kutlwano Olifant, ‘Alleged assault of former girlfriend lands DJ in court,’ The Star, 15 July 2012.

[4] TSHISALIVE, ‘Bonang Matheba: I hit rock bottom in 2012,’ Times Live, 18 September 2017.

[5] Karabo Malofo, ‘“Twitter feels safe” to abuse victims,’ Daily Maverick, 13 January 2021.

[6] Lucinda Dordley, ‘Another allegation of rape levelled against DJ Fresh,’ Capetownetc., 19 February 2021.

[7] Emmanuel Tjyia, ‘Rape charges against DJ Fresh and Euphonik withdrawn,’ Sowetan Live, 15 February 2021.

[8] Lisa Vetten et al., Tracking Justice: The attrition of rape cases through the criminal justice system in Gauteng, Johannesburg (Tshwaranang Legal Advocay Centre, 2008).

[9] Alexandra Topping and Caelainn Barr, ‘Rape convictions fall to record low in England and Wales,’ The Guardian, 30 July 2020.

[10] Llu Tladi, 15 February 2021, 6:01PM; Terry Mthembu, 15 February 2021, 6:52PM.

[11] Sandisiwe Mbhele, “Star witness’ in Fresh, Euphonik rape case claims no knowledge of incident,’ The Citizen, 18 February 2021.

[12] JBourke, Rape, 392.

[13] Bourke, Rape, 28-29; 396.

[14] Elizabeth Kolsky, ‘‘The Body Evidencing the Crime’: Rape on Trial in Colonial India, 1860-1947,’ Gender & History 22:1 (2010): 114.

[15] Timothy Keegan, ‘Gender, Degeneration and Sexual Danger: Imagining Race and Class in South Africa, ca. 1912,’ Journal of Southern African Studies 27: 3 (2001): 464; Pumla Dineo Gqola, Rape: A South African Nightmare (Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2015), 43.

[16] Gqola, Rape, 43.

[17] Rand Daily Mail, 2 August 1972.

[18] Wits Historical Papers AD1912A/W270.2, Enoch Duma, ‘The boy who had to rape his mother’, 5 June 1977.

[19] See Ike Motsapi, ‘Rape: Women face an agonizing decision,’ Soweto News, 12 February 1982; Themba Khumalo, ‘155 fall victim to rape says Viktor,’ The Star, 15 April 1983.

[20] Redi Tlhabi, Khwezi – The Remarkable Story of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo (Johannesburg: Media24, 2017).