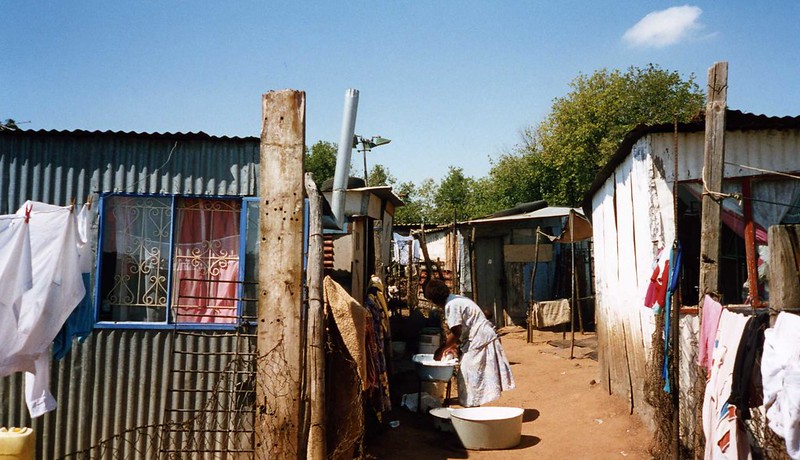

Much of the best academic research on rape over the past decade, in South Africa and globally, has focused explicitly on men, the primary perpetrators of sexual violence. Such efforts have resulted in truly important work; understanding why men rape is essential to combatting sexual violence. Furthermore, focusing on rapists helps hold them to account. Rape is often reported as a ‘perpetrator-less crime’, with undue attention paid to female victims – where they were, what they were wearing, or how they were behaving – rather than the men who most commonly inflict this violence. [1] Joanna Bourke contends that ‘it would be wrong to explore the violence carried out predominantly by men by studying the women they wound,’ arguing that doing so may only perpetuate tendencies to blame women for their own violation. [2] When specific research on rape in South Africa began in the 1990s, the primary focus was also on the rapist. [3] More recently, researchers have tried to establish exactly who the country’s rapists are, interviewing men from across various class, educational, and ethnic backgrounds, and why they commit this violence, exploring theories of masculinities ‘in crisis’, past-perpetrator trauma, socio-economic exclusion, and patriarchal gender norms. [4]